The Immortal Boy by Francisco Montana Ibanez, translated by David Bowles.

Levine Querido, New York, 2021.

Billingual fiction, 154 pages English, 154 pages Spanish.

Not yet leveled.

Two stories in Bogota, Colombia: five siblings try to stay together in their father’s absence, and a girl left in an orphanage follows a child called The Immortal Boy.

After rejecting the overwhelming stereotypes of Villoro’s The Wild Book, I was still searching for a Latine youth fantasy novel in translation. I respect David Bowles and had seen this mentioned without a clear age range, so hoped it would work for my diverse MG fantasy booklists.

Alas, it would be a stretch to consider this MG, although it may be suitable for individual readers. The Immortal Boy is disturbing and morbid… but still good? A difficult book to put down and also an emotionally challenging read. The story is one of nearly unrelenting misery, yet paradoxically beautifully written.

But allow me a moment to consider the presentation. Although I’d started two other books from Levine Querido without realizing, this was my first conscious purchase from the imprint. LQ books are not cheap, but are good quality with thick paper, carefully chosen typography, and great attention to detail.

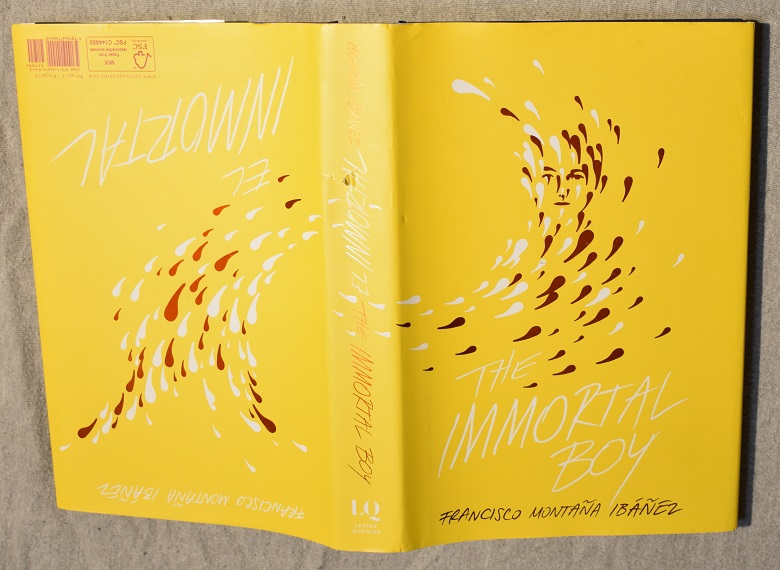

Nowhere is this more apparent than the design. This book is presented in both English and Spanish within the same volume, so the dust jacket uses a flipbook style. As I do not speak any language other than English fluently enough to fully analyze a work’s literary merits, this review will focus on the English version.

While the cover design at first appears merely appealing, after reading it’s clear much thought was put into interpreting the book’s themes. The English version is the primary cover (the Spanish side has the barcode for scanning) but both are appealing and the spine is designed to work in either direction. The two covers are also connected and tie together.

Oldest boy Hector, a young 13, lied about his age for a job unloading bulk vegetables. Leaving school to work means no school lunches, so he dreams of eating just one or two of the many potatoes he moves. Cooking, childcare, and home maintenance fall to oldest girl Maria, who also has an unofficial, occasional job working as a shop clerk which pays only in food and favors.

Despite being youngest and presumably needing the least food, five year old Manuela is closest to starvation since she is not yet able to attend school, and thus not assured of even one daily meal. In the middle are Robert, who thinks only of food and will do anything – ANYTHING to eat or stop thinking of food, and his younger brother David, who is stronger and more competent but still a child who doesn’t always think through consequences.

Life for these five children moves in small increments, with a step for the better and two steps for the worse – as their father is away longer and longer, their efforts to gain and stretch food become more of a struggle and they grow closer to starvation. The outside world is mainly one of unrelenting cruelty, and perhaps the cruelest adults are those who make the children feel hope while failing to provide any real change in their circumstances.

Every other chapter abruptly switches from omniscient third person narration to the first person musings of Nina. Her life at the orphanage is regimented and cold, but in comparison to the alternating chapters often seems downright pleasant. Yet in her daily activities we see glimpses of deep trauma, both in Nina herself, and those around her. Having come from a two parent home and with a mother presumably returning for her, Nina is considerably better off than many, but even the act of being institutionalized is slowly altering her.

After a bullying incident goes wrong, Nina becomes obsessed with the idea of befriending the silent loner who helped her – no matter what that involves. This obsession builds until the chilling conclusion, where we finally understand how these different characters connect, but don’t receive any real answers.

I’m avoiding saying much about the plot. Partly that is because it’s difficult to discuss any of the major points without giving away the journey. Partly I don’t desire to discuss unrelenting misery. For those of you who have already read the story, or prefer major spoilers before reading, this interview may be helpful – it certainly helped me to solidify my own thoughts about the work.

Originally I thought that the Spanish version was simply the original work. After reading the interview where the author mentions translation for the North American context, and considering David Bowles works in both English and Spanish, and that the title was changed, I am not entirely sure on this point. Perhaps somebody who read the original would comment.

Content warnings (major spoilers): abandonment of children, abuse of children, starvation, gang life, theft, wage slavery, drug use (including by children), smoking, swearing, societal malaise, fighting, death by gun violence, fratricide, self-harm, bullying, political imprisonment, poisoning, alcohol poisoning, consumption of non-food items, traumatic death of animals, flirtation, and more.

I’m at a loss as to whom this was written for, and am not likely to reread again myself, yet… it serves as a vivid reminder that innovation is still happening in youth literature, and brings up important topics. I could see this in high school classrooms, but would be hesitant to broadly recommend it for middle school. Definitely pre-read and be prepared for difficult conversations.

Perhaps horror readers might find more to return to here – it certainly sent a chill down my spine.